Background

syzkaller is an amazing tool for kernel fuzzing. Besides, it is quite easy to set up and start running to find bugs. However, to get yourself more familiar with this tool and find more bugs, we have to learn some details about it.

This post is the first one of syzkaller diving, you’ll learn how the coverage of KCOV works and how it guides syzkaller.

KCOV 101

The basic usage of kcov can be found in the official manual (Possibly for fuzzing). Below is one example with annotations.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#define KCOV_INIT_TRACE _IOR('c', 1, unsigned long)

#define KCOV_ENABLE _IO('c', 100)

#define KCOV_DISABLE _IO('c', 101)

#define COVER_SIZE (64<<10)

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int fd;

uint32_t *cover, n, i;

/* A single fd descriptor allows coverage collection on a single

* thread.

*/

fd = open("/sys/kernel/debug/kcov", O_RDWR);

if (fd == -1)

perror("open");

/* Setup trace mode and trace size. */

if (ioctl(fd, KCOV_INIT_TRACE, COVER_SIZE))

perror("ioctl");

/* Mmap buffer shared between kernel- and user-space. */

cover = (uint32_t*)mmap(NULL, COVER_SIZE * sizeof(uint32_t),

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if ((void*)cover == MAP_FAILED)

perror("mmap");

/* Enable coverage collection on the current thread. */

if (ioctl(fd, KCOV_ENABLE, 0))

perror("ioctl");

/* Reset coverage from the tail of the ioctl() call. */

__atomic_store_n(&cover[0], 0, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

/* That's the target syscal call. */

read(-1, NULL, 0);

/* Read number of PCs collected. */

n = __atomic_load_n(&cover[0], __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

/* PCs are shorten to uint32_t, so we need to restore the upper part. */

for (i = 0; i < n; i++)

printf("0xffffffff%0lx\n", (unsigned long)cover[i + 1]);

/* Disable coverage collection for the current thread. After this call

* coverage can be enabled for a different thread.

*/

if (ioctl(fd, KCOV_DISABLE, 0))

perror("ioctl");

/* Free resources. */

if (munmap(cover, COVER_SIZE * sizeof(uint32_t)))

perror("munmap");

if (close(fd))

perror("close");

return 0;

}

This example is much or less self-explanatory: You have to open the kcov file, then you need to use ioctl to interact with it. Before you start, you need first to mmap a buffer to collect information and then set KCOV_ENABLE. After that, do what you what to fuzz. When the operations are over, you can start to parse the collected information. The first integer is the number of collected PCs and the following member of the arrays are what kcov collected. After all of that, you can set KCOV_DISABLE and have a great relaxation.

Cool, let us now take a peek at how these things are done in the kernel. All relevant functions are presented in kernel/kcov.c.

/*

* Entry point from instrumented code.

* This is called once per basic-block/edge.

*/

void notrace __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc(void)

{

struct task_struct *t;

unsigned long *area;

unsigned long ip = canonicalize_ip(_RET_IP_);

unsigned long pos;

t = current;

if (!check_kcov_mode(KCOV_MODE_TRACE_PC, t))

return;

area = t->kcov_area;

/* The first 64-bit word is the number of subsequent PCs. */

pos = READ_ONCE(area[0]) + 1;

if (likely(pos < t->kcov_size)) {

area[pos] = ip;

WRITE_ONCE(area[0], pos);

}

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL(__sanitizer_cov_trace_pc);

// ...

static void kcov_start(struct task_struct *t, struct kcov *kcov,

unsigned int size, void *area, enum kcov_mode mode,

int sequence)

{

kcov_debug("t = %px, size = %u, area = %px\n", t, size, area);

t->kcov = kcov;

/* Cache in task struct for performance. */

t->kcov_size = size;

t->kcov_area = area;

t->kcov_sequence = sequence;

/* See comment in check_kcov_mode(). */

barrier();

WRITE_ONCE(t->kcov_mode, mode);

}

static void kcov_stop(struct task_struct *t)

{

WRITE_ONCE(t->kcov_mode, KCOV_MODE_DISABLED);

barrier();

t->kcov = NULL;

t->kcov_size = 0;

t->kcov_area = NULL;

}

As you can see, when kcov_start is executed, additional structure kcov will be bind to the task_struct of which process that set KCOV_ENABLE.

After that, every hook function __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc can take effects because check_kcov_mode(KCOV_MODE_TRACE_PC, t) returns TRUE for now on. What this trace does is quite simple like below.

area = t->kcov_area;

/* The first 64-bit word is the number of subsequent PCs. */

pos = READ_ONCE(area[0]) + 1;

if (likely(pos < t->kcov_size)) {

area[pos] = ip;

WRITE_ONCE(area[0], pos);

}

That’s it, the __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc will read the first integer from the array (as we also do in userspace), write hooked PC to the next slot, and update the first integer.

How __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc is inserted into kernel is about CONFIG_KCOV. If you enable this configuration, the compile will adopt the flag of -fsanitize-coverage=trace-pc to build the kernel. This plugin is located at scripts/gcc-plugins/sancov_plugin.c of your kernel source code.

One interesting try is you can write your own __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc to allow extended features. For example, you can easily write a userspace library to offer __sanitizer_cov_trace_pc function and allow your userspace function to be traced.

KCOV and syzkaller

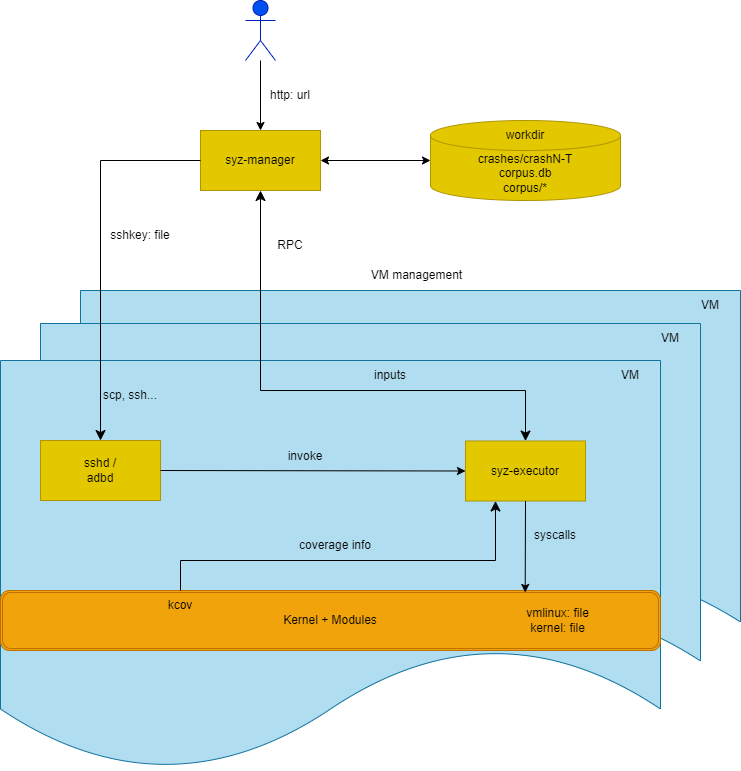

So far we know how to operate on kcov, we next want to unhide how syzkaller adopts it. From a high level, as demonstrated in syzkaller’s official documentation as below, the coverage is collected by syz-fuzzer to decide better programs.

how syz-fuzzer gets the coverage

As we discuessed above, the kcov need to be collected according to the task_struct. Hence, the very concern about kcov is the syz-executor. We can find code below

// executor/executor_linux.h

static void cover_open(cover_t* cov, bool extra)

{

int fd = open("/sys/kernel/debug/kcov", O_RDWR);

if (fd == -1)

fail("open of /sys/kernel/debug/kcov failed");

if (dup2(fd, cov->fd) < 0)

fail("filed to dup2(%d, %d) cover fd", fd, cov->fd);

close(fd);

const int kcov_init_trace = is_kernel_64_bit ? KCOV_INIT_TRACE64 : KCOV_INIT_TRACE32;

const int cover_size = extra ? kExtraCoverSize : kCoverSize;

if (ioctl(cov->fd, kcov_init_trace, cover_size))

fail("cover init trace write failed");

size_t mmap_alloc_size = cover_size * (is_kernel_64_bit ? 8 : 4);

cov->data = (char*)mmap(NULL, mmap_alloc_size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, cov->fd, 0);

if (cov->data == MAP_FAILED)

fail("cover mmap failed");

cov->data_end = cov->data + mmap_alloc_size;

}

This function opens relevant file, duplicates the descriptor, inits the kocv and creates the shared buffer. By back slicing we know this function is called by the main of syz-executor.

static void cover_enable(cover_t* cov, bool collect_comps, bool extra)

{

unsigned int kcov_mode = collect_comps ? KCOV_TRACE_CMP : KCOV_TRACE_PC;

// The KCOV_ENABLE call should be fatal,

// but in practice ioctl fails with assorted errors (9, 14, 25),

// so we use exitf.

if (!extra) {

if (ioctl(cov->fd, KCOV_ENABLE, kcov_mode))

exitf("cover enable write trace failed, mode=%d", kcov_mode);

return;

}

if (is_kernel_64_bit)

enable_remote_cover<uint64_aligned64>(cov, KCOV_REMOTE_ENABLE64, kcov_mode);

else

enable_remote_cover<uint64_aligned32>(cov, KCOV_REMOTE_ENABLE32, kcov_mode);

}

The cover_enable function is expected to set KCOV_ENABLE. It is called before execute_call function.

Besides, you can see enable_remote_cover here, we will explain this in future posts.

static void cover_collect(cover_t* cov)

{

if (is_kernel_64_bit)

cov->size = *(uint64*)cov->data;

else

cov->size = *(uint32*)cov->data;

}

The cover_collect function will update manager structure according to the created buffer.

For now, the above details are enough to understand the workflow. From the figure, we see that coverage is transferred to syz-fuzzer and the below function is to take responsibility for that.

template <typename cover_data_t>

void write_coverage_signal(cover_t* cov, uint32* signal_count_pos, uint32* cover_count_pos)

{

// Write out feedback signals.

// Currently it is code edges computed as xor of two subsequent basic block PCs.

cover_data_t* cover_data = ((cover_data_t*)cov->data) + 1;

uint32 nsig = 0;

cover_data_t prev = 0;

for (uint32 i = 0; i < cov->size; i++) {

cover_data_t pc = cover_data[i];

if (!cover_check(pc)) {

debug("got bad pc: 0x%llx\n", (uint64)pc);

doexit(0);

}

cover_data_t sig = pc ^ prev;

prev = hash(pc);

if (dedup(sig))

continue;

write_output(sig);

nsig++;

}

// Write out number of signals.

*signal_count_pos = nsig;

if (!flag_collect_cover)

return;

// Write out real coverage (basic block PCs).

uint32 cover_size = cov->size;

if (flag_dedup_cover) {

cover_data_t* end = cover_data + cover_size;

cover_unprotect(cov);

std::sort(cover_data, end);

cover_size = std::unique(cover_data, end) - cover_data;

cover_protect(cov);

}

// Truncate PCs to uint32 assuming that they fit into 32-bits.

// True for x86_64 and arm64 without KASLR.

for (uint32 i = 0; i < cover_size; i++)

write_output(cover_data[i]);

*cover_count_pos = cover_size;

}

// ...

uint32* write_output(uint32 v)

{

if (output_pos < output_data || (char*)output_pos >= (char*)output_data + kMaxOutput)

fail("output overflow: pos=%p region=[%p:%p]",

output_pos, output_data, (char*)output_data + kMaxOutput);

*output_pos = v;

return output_pos++;

}

You may be interested in what will happen about output_pos pointer. In fact, it points to memory mmaped from kOutFd. What means these collected infomation (including coverage) will be stored into a file. The file is specified by the syz-fuzzer when it creates the fuzzing command.

func makeCommand(pid int, bin []string, config *Config, inFile, outFile *os.File, outmem []byte,

tmpDirPath string) (*command, error) // outFile is what we know as kOutfd

So the coverage is collected by the syz-executor and be written into a file, which then be parsed and used by syz-fuzzer.

how syz-fuzzer uses the coverage

Coverage-guided fuzzing is cool, but how the coverage guide the fuzzer? We will see that in a short time.

For a Program (couples of system calls), the syzkaller will triage it to decide if it can be added to the corpus. This is done by function triageInput

func (proc *Proc) triageInput(item *WorkTriage) {

log.Logf(1, "#%v: triaging type=%x", proc.pid, item.flags)

prio := signalPrio(item.p, &item.info, item.call)

inputSignal := signal.FromRaw(item.info.Signal, prio)

newSignal := proc.fuzzer.corpusSignalDiff(inputSignal)

if newSignal.Empty() {

return

}

callName := ".extra"

logCallName := "extra"

if item.call != -1 {

callName = item.p.Calls[item.call].Meta.Name

logCallName = fmt.Sprintf("call #%v %v", item.call, callName)

}

log.Logf(3, "triaging input for %v (new signal=%v)", logCallName, newSignal.Len())

var inputCover cover.Cover

const (

signalRuns = 3

minimizeAttempts = 3

)

// Compute input coverage and non-flaky signal for minimization.

notexecuted := 0

for i := 0; i < signalRuns; i++ {

info := proc.executeRaw(proc.execOptsCover, item.p, StatTriage) // [A]

if !reexecutionSuccess(info, &item.info, item.call) {

// The call was not executed or failed.

notexecuted++

if notexecuted > signalRuns/2+1 {

return // if happens too often, give up

}

continue

}

thisSignal, thisCover := getSignalAndCover(item.p, info, item.call)

newSignal = newSignal.Intersection(thisSignal)

// Without !minimized check manager starts losing some considerable amount

// of coverage after each restart. Mechanics of this are not completely clear.

if newSignal.Empty() && item.flags&ProgMinimized == 0 {

return

}

inputCover.Merge(thisCover)

}

if item.flags&ProgMinimized == 0 { // [B]

item.p, item.call = prog.Minimize(item.p, item.call, false,

func(p1 *prog.Prog, call1 int) bool {

for i := 0; i < minimizeAttempts; i++ {

info := proc.execute(proc.execOptsNoCollide, p1, ProgNormal, StatMinimize)

if !reexecutionSuccess(info, &item.info, call1) {

// The call was not executed or failed.

continue

}

thisSignal, _ := getSignalAndCover(p1, info, call1)

if newSignal.Intersection(thisSignal).Len() == newSignal.Len() {

return true

}

}

return false

})

}

data := item.p.Serialize()

sig := hash.Hash(data)

log.Logf(2, "added new input for %v to corpus:\n%s", logCallName, data)

proc.fuzzer.sendInputToManager(rpctype.RPCInput{

Call: callName,

Prog: data,

Signal: inputSignal.Serialize(),

Cover: inputCover.Serialize(),

})

proc.fuzzer.addInputToCorpus(item.p, inputSignal, sig) // [C}]

if item.flags&ProgSmashed == 0 {

proc.fuzzer.workQueue.enqueue(&WorkSmash{item.p, item.call})

}

}

From the very high level, we can see that if the update signal interacts with existing signals can output new signals, it will admit this input and add it to the corpus.

Then the question is raised, what is the signal here? Okay, it’s another way of expressing the coverage. We can see the source code below

// ......

// Write out feedback signals.

// Currently it is code edges computed as xor of two subsequent basic block PCs.

cover_data_t* cover_data = ((cover_data_t*)cov->data) + 1;

uint32 nsig = 0;

cover_data_t prev = 0;

for (uint32 i = 0; i < cov->size; i++) {

cover_data_t pc = cover_data[i];

if (!cover_check(pc)) {

debug("got bad pc: 0x%llx\n", (uint64)pc);

doexit(0);

}

cover_data_t sig = pc ^ prev;

prev = hash(pc);

if (dedup(sig))

continue;

write_output(sig);

nsig++;

}

// ......

Hence new signal means there is a new path with unexplored basic blocks! Once this program is added into Corpus, It can further help to motivate the next mutation.

At last, we will take a look at how syzkaller mutate the fuzzer inputs (prog/mutation.go)

// Mutate program p.

//

// p: The program to mutate.

// rs: Random source.

// ncalls: The allowed maximum calls in mutated program.

// ct: ChoiceTable for syscalls.

// corpus: The entire corpus, including original program p.

func (p *Prog) Mutate(rs rand.Source, ncalls int, ct *ChoiceTable, corpus []*Prog) {

r := newRand(p.Target, rs)

if ncalls < len(p.Calls) {

ncalls = len(p.Calls)

}

ctx := &mutator{

p: p,

r: r,

ncalls: ncalls,

ct: ct,

corpus: corpus,

}

for stop, ok := false, false; !stop; stop = ok && len(p.Calls) != 0 && r.oneOf(3) {

switch {

case r.oneOf(5): /* 1/5 */

// Not all calls have anything squashable,

// so this has lower priority in reality.

ok = ctx.squashAny()

case r.nOutOf(1, 100):

ok = ctx.splice() /* 1/100 * 4/5 */

case r.nOutOf(20, 31):

ok = ctx.insertCall() /* 20/31 * 4/5 * 99/100 */

case r.nOutOf(10, 11):

ok = ctx.mutateArg() /* 10/11 * 4/5 * 99/100 * 10/31 */

default:

ok = ctx.removeCall() /* 4/5 * 99/100 * 10/31 * 1/10 */

}

}

p.sanitizeFix()

p.debugValidate()

if got := len(p.Calls); got < 1 || got > ncalls {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("bad number of calls after mutation: %v, want [1, %v]", got, ncalls))

}

}

Let’s take a simple look at this mutation

// This function selects a random other program p0 out of the corpus, and

// mutates ctx.p as follows: preserve ctx.p's Calls up to a random index i

// (exclusive) concatenated with p0's calls from index i (inclusive).

func (ctx *mutator) splice() bool {

/* ... */

// Picks a random complex pointer and squashes its arguments into an ANY.

// Subsequently, if the ANY contains blobs, mutates a random blob.

func (ctx *mutator) squashAny() bool {

/* ... */

// Inserts a new call at a randomly chosen point (with bias towards the end of

// existing program). Does not insert a call if program already has ncalls.

func (ctx *mutator) insertCall() bool {

/* ... */

// Removes a random call from program.

func (ctx *mutator) removeCall() bool {

/* ... */

// Mutate an argument of a random call.

func (ctx *mutator) mutateArg() bool {

/* ... */

In fact, the mutation of the system call is not an easy job and the different operations supplied by syzkaller may not be the most ideal one (but can take good effect for sure ;d ).

Summary

In this blog, we firstly dive into syzkaller and learn how the coverage (kcov) works in it. The insight of this will lighten us to write other tools to fuzz target like system calls.